Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

Heart failure is a common comorbidity with the greatest prevalence in the older population. Heart failure is often the end stage of the cardiovascular trajectory and is associated with a poor prognosis and quality of life. The good news is that if heart failure is diagnosed early enough, healthcare professionals can make a huge difference to both the quantity and quality of life for patients.

Case study

A 78-year-old male, who was previously independent, had noticed he was increasingly breathless for six months. He collapsed whilst digging in his allotment. A friend rang 999 and paramedics at the scene found him to be in ventricular fibrillation arrest. He was successfully resuscitated and taken to the accident and emergency department.

[rml_read_more]

An echocardiogram was done soon after his admission. It showed that only 25% of his left ventricle was being expelled after each systole. Anything under 55% is abnormal, anything under 40% is referred to as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

This patient should have been diagnosed many years earlier, but instead his heart failure developed insidiously, and he later died.

Is heart failure more malignant than cancer?

A study examined whether heart failure was more malignant than cancer. It found that – with the notable exception of lung cancer – heart failure is as ‘malignant’ as many common types of cancer and is associated with a comparable number of expected life-years lost.1

The study included patients with a first admission to any Scottish hospital in 1991 for heart failure, myocardial infarction or the four most common types of cancer specific to men and women. Five-year survival rates and associated loss of expected life-years were then compared.

It found that 16,224 men had an initial hospitalisation for heart failure (n=3,241), myocardial infarction (n=6,932) or cancer of the lung, large bowel, prostate or bladder (n=6,051). Similarly, 14,842 women were admitted for heart failure (n=3,606), myocardial infarction (n=4,916), or cancer of the breast, lung, large bowel or ovary (n=6,320).

With the exception of lung cancer, heart failure was associated with the poorest 5-year survival rate (approximately 25% for both sexes). On an adjusted basis, heart failure was associated with worse long-

term survival than bowel cancer in men and breast cancer in women.1

Greater access to echocardiography

The NHS Long Term Plan says that people with heart failure and heart valve disease will be better supported by multi-disciplinary teams as part of primary care networks. It adds that 80% of heart failure is currently diagnosed in hospital, despite 40% of patients having symptoms that should have triggered an earlier assessment.2

As a result, it recommends greater access to echocardiography in primary care and says this will improve the investigation of those with breathlessness, and the early detection of heart failure and valve disease.

When older patients present to primary care with breathlessness, GPs have to consider both the heart and lungs. Important considerations are chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), atrial fibrillation and aortic stenosis.

Aortic stenosis, for example, is the most preventable form of impending heart failure. Due to the advent of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), patients are usually allowed home a few days later with fairly normal life expectancy. Optimal outcomes in aortic stenosis, however, require timely referral for intervention.3-5

There is a rising burden of valve disease making it an important public-health problem. A Lancet study found that moderate or severe valvular diseases are notably common and increase with age. In the community, women are less often diagnosed than are men, which could indicate an important imbalance in view of the associated lower survival.6

There has also been an evolution of different types of valve disease in the developed world. We hardly see rheumatic valve disease, but due to the ageing population, we are going to see different forms of degenerative valve disease emerging.7

The main cause of breathlessness (dyspnoea) is COPD. We have got quite good at diagnosing COPD due to spirometry, but it is important not to miss the coexisting heart failure.

Cardiac causes of breathlessness include heart failure, arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation) and valve disease (aortic stenosis and mitral regurgitation). Pulmonary causes include asthma, COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, lung cancer and recurrent pulmonary embolism. Other causes are deconditioning /obesity, anaemia, hyperthyroidism,and anxiety.

Heart failure is not just a mechanical ‘pump failure’

We now think of heart failure as a clinical syndrome and not just as a mechanical ‘pump failure’. Symptoms and signs include breathlessness, fatigue and fluid retention. Most heart failure patients have reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of <40%, but many will have clinical heart failure with a normal or near normal ejection fraction of >50%.

Heart failure is also associated with a range of comorbidities such as obesity, obstructive sleep apnoea, hypertension, diabetes and atrial fibrillation.

Overwhelming efficacy of medical therapy

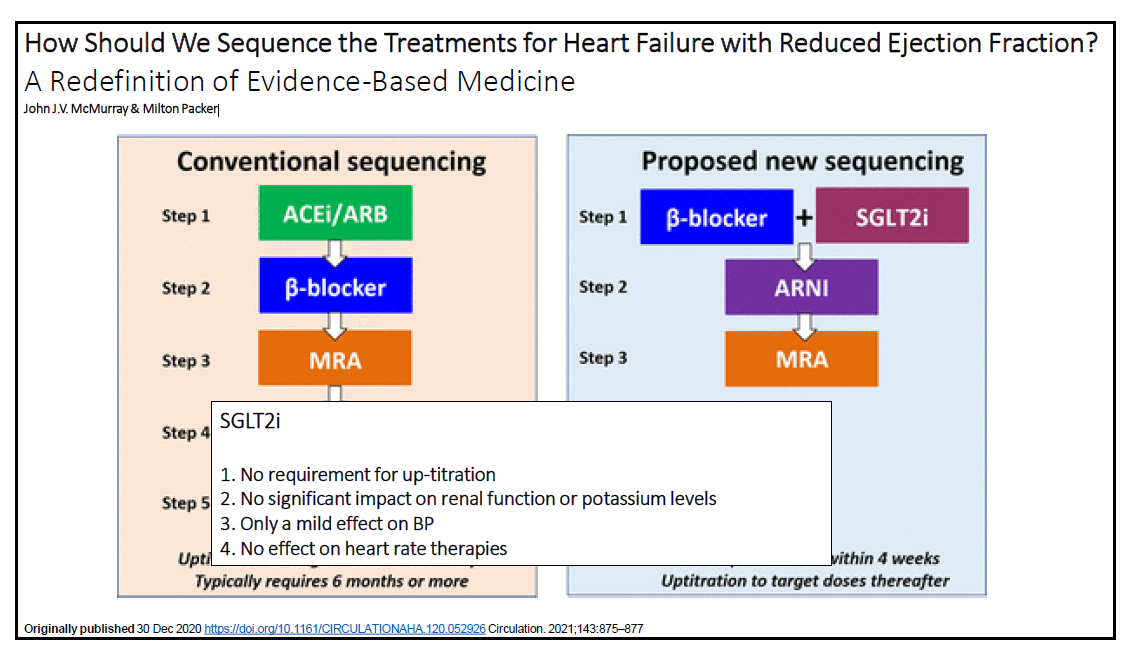

By sequentially adding angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers, and aldosterone antagonists – along with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in some cases – the life expectancy and the risk of hospitalisation is greatly reduced in heart failure patients.8

For this reason, it cannot be just cardiologists who deal with heart failure. It is such a common condition that it should be routine clinical practice across all specialties and definitely in primary care.

Heart failure treatment has evolved in recent years. In 1987, there were only two licenced treatments for heart failure in the UK – diuretics and digoxin – and neither of these improved patients’ symptoms. By 2022, the toolbox included diuretics, ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) (also known as aldosterone antagonists), angiotensin receptor II blockers (Entresto), sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, ivabradine, ventricular assist devices, cardiac resynchronisation, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) and cardiac transplantation.

The most exciting upgrade to heart failure treatment has been the SGLT2s. This is a class of therapy likely to give tremendous cardiovascular benefit in many scenarios.

The DAPA-HF trial with dapagliflozin included over 4,000 patients who had a New York Heart Association class II, III, or IV heart failure and an ejection fraction of 40% or less.

The patients either received dapagliflozin (at a dose of 10mg once daily) or placebo, in addition to recommended therapy. The primary outcome was a composite of worsening heart failure (hospitalisation or an urgent visit resulting in intravenous therapy for heart failure) or cardiovascular death.9

The risk of worsening heart failure or death from cardiovascular causes was lower among those who received dapagliflozin than among those who received placebo, regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes.

In the EMPEROR-Reduced trial, empagliflozin had similar results. Among patients receiving recommended therapy for heart failure, those in the empagliflozin group had a lower risk of cardiovascular death or hospitalisation for heart failure than those in the placebo group, regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes.10

Implications for guidelines

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has now given both these drugs a class one recommendation and they are recommended as part of the four pillars of treatment for heart failure with ACE inhibitors/ARNI, beta-blockers and MRAs.11

There is also a proposed new sequencing of heart failure drugs. At the moment, if you start optimising all of these drugs in the order of the evidence base, it can take at least six months to get to optimisation, which is not helpful for patients. (Figure 1).12

It is thought that the new sequencing of including a SGLT2 earlier will maximise the likelihood that highly effective therapies will be implemented in a manner that rapidly prevents deaths and hospitalisations and enhances the tolerability of concurrently or subsequently administered treatments.

Dr Yassir Javaid, GPwSI Cardiology & Cardiovascular Lead, Northampton-shire Integrated Care Board

GM editorial team

References

- Stewart S et al. Eur. J Heart Failure (2001); 3: 315-32217

- https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/online-version/chapter-3-further-progress-on-care-quality-and-outcomes/

- Carabello BA. Introduction to aortic stenosis. CircRes 2013; 113: 179–85

- Ross J Jr, BraunwaldE. Aortic stenosis. Circulation 1968; 38: 61–7

- Turina J, et al. Spontaneous course of aortic valve disease. Eur Heart J 1987; 8: 471–83

- Enriquez-Sarano M, et al. The Lancet, 2006; 368(9540: 1005 -1011

- Soler-Soler J, Galve E. Worldwide perspective of valve disease. Heart 2000; 83: 721–5

- Levy W, et al. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation 2006; 113: 1424-1433

- McMurray J, et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1995-2008

- Packer M, et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1413-1424

- ESC. https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Acute-and-Chronic-Heart-Failure (accessed 12/04/23)

- McMurray JJV, et al. How Should We Sequence the Treatments for Heart Failure and a Reduced Ejection Fraction?: A Redefinition of Evidence-Based Medicine. Circulation 2021; 143(9): 875-77