Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

One third of people with a healthy body mass index (BMI) are obese and at high risk of cardiometabolic diseases, according to a new study by researchers at Tel Aviv University (TAU).1

The study found that obesity with ‘normal weight’ is much more common that previously assumed, and the authors are now calling for clinicians to move away from measuring BMI and towards measuring body fat percentage.

The problem with BMI

BMI is a measure widely used in clinical practice to determine whether a patient is a healthy weight for their height.

[rml_read_more]

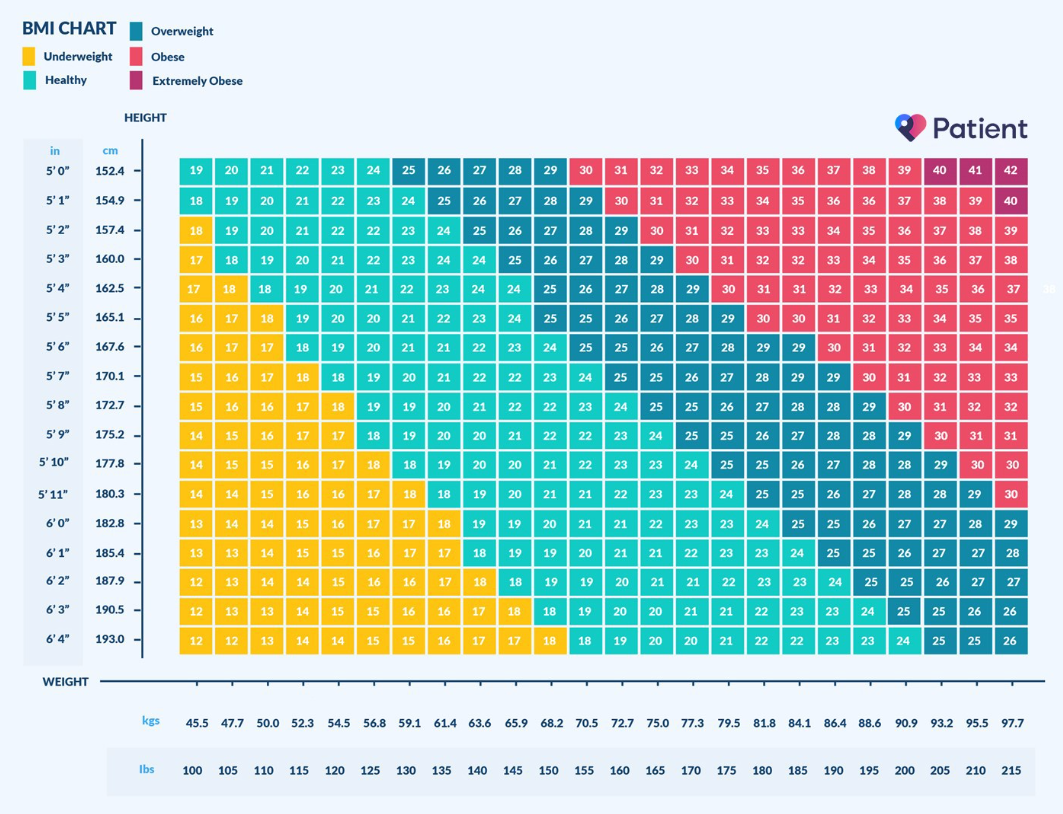

The index uses a simple mathematical formula which provides a value derived from the mass and height of a person. The measure categorises people into five groups: underweight (<18.5), healthy weight (18.5-24.9), overweight (25-29.9), obese (30-34.9) and severely obese (35<).

The measure has been widely used in clinical practice since the 1970s, replacing previously diverse and contested definitions of excess body weight.2

However, the tool fails to account for overall fat or lean tissue content. Muscle is roughly 18% more dense than fat, and therefore weighs more by volume.3 This means people with high muscle mass and normal body fat percentage may therefore have a high BMI, when in reality, they are perfectly healthy.

For example, an Olympic athlete who is 6ft tall and weighs 96kg would have a BMI of 28, classifying them as overweight. Whereas someone of the same height with less muscle and a higher body fat percentage may have a lower BMI, and be classified as a healthy weight.4

There is therefore a clear flaw in the way that BMI categorises people into ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ weight groups. So, is it time to start using a new method to measure health in clinical practice?

A new way of measuring body fat

BMI has proved a useful tool over the last few decades, particularly when body composition analyses did not exist.

Now, DXA (Dual X-ray Absorptiometry) scans can quickly provide an in-depth analysis of patients’ fat tissue, lean mass and bone density. DXA scans are quick and pain free and can be completed within six to 10 minutes.5

The researchers at TAU who conducted the study said DXA scans and other tools which measure body fat percentage should now become the “gold standard” to measure body composition, and recommend all GPs and clinics are equipped with such devices.1

This is because many patients who are at risk of health problems are currently flying under the radar, and may be missing out on vital treatments to improve their health.

“Unlike people who are identified as overweight, they receive no treatment or instructions for changing their nutrition or lifestyle – which places them at an even greater risk for cardiometabolic diseases,” said Prof. Yftach Gepner, lead author of the study.

Indeed, the study of 3,000 participants found that one third of the participants, 1,000 individuals, were found to be within the normal weight range. Of these, 38.5% of the women and 26.5% of the men were identified as ‘obese with normal weight’ – having excess fat content despite their normal weight.1

According to the researchers, the actual measure for obesity is the body’s fat content, with the maximum normal values set at 25% for males and 35% for females.1

Matching body fat percentage with blood markers for each of these individuals, the study found a significant correlation between ‘obesity with normal weight’ and high levels of sugar, fat, and cholesterol – major risk factors for a range of cardiometabolic diseases.1

“Higher fat content is defined as obesity and can cause a range of potentially life-threatening cardiometabolic diseases: heart disease, diabetes, fatty liver, kidney dysfunction, and more,” Prof. Gepner said.

“The disparity between the two indexes has generated a phenomenon called ‘the paradox of obesity with normal weight’ – higher than normal body fat percentage in normal-weight individuals. In this study we examined the prevalence of this phenomenon in Israel’s adult population,” he added.

The study also found that BMI can inaccurately define people as overweight or obese, despite having a normal body fat percentage. The study found that 30% of the men and 10% of the women identified as overweight were found to have a normal body fat percentage. This is common in tall people with high percentages of lean mass.1

Prof. Gepner says the findings are “somewhat alarming” and is calling for body fat percentage to become the prevailing standard of health.

However, there is high variability in access to, and quality of, DXA scans worldwide.6 While the number of DXA machines is relatively high in Europe, an audit of the Middle East and Africa found that access to DXA machines was extremely limited, with most countries estimating the availability to be less than five machines per million of the population.7

Measuring body fat without a DXA scan

While we wait for DXA scans to become more widely available, there are other measures clinicians can undertake alongside measuring weight and height.

According to the British Heart Foundation, skinfold calipers, which measure the thickness of subcutaneous fat, are the “cheapest, easiest and most portable method to measure body fat in specific areas.”8

Fat is normally measured using at least three spots on the body. The clinician will pinch the skin, pulling the muscle away from the fat, and measure the fold with the calipers. The measurements are then put into an online calculator to give the body fat percentage.

It is important to note that the accuracy of this measurement depends on the skills of the person taking the measurement, and it may be difficult to get a reliable result in obese people.

Clinicians may also measure the patient’s waist circumference and the waist to hip ratio. For both measurements, all that it’s needed is a measuring tape.8

When measured properly, calculating the waist circumference is typically accurate within 5% of the body fat value measured using underwater weighing. This is one of the most accurate ways of measuring body composition, but is typically only performed on athletes or for research purposes.8

Measuring the ratio of waist circumference to the hip circumference allows healthcare professionals to determine whether the patient is at a high risk of an adverse health event. The higher the ratio, the more fat is stored around the waist or abdomen, posing a greater health risk than fat stored elsewhere in the body.

However, while these methods can accurately measure excess body fat, it is still not a precise measurement of body composition, and this is why DXA scans are considered the ‘gold standard’ measurement.

Devices that measure the body’s electrical conductivity are also commonly used in many fitness centres, however, at-home body fat devices are often inaccurate. This is because hydration plays a major role in this reading, and a person who is not adequately hydrated may show a higher body fat percentage than is actually accurate, and a person who is overly hydrated might get a number too low.9

Should weight loss drugs be prescribed based on body fat percentage instead of BMI?

Healthcare professionals typically use BMI to help decide whether a patient might benefit from weight management medications.

Healthcare professionals may prescribe a medication to treat overweight or obesity if the patient is classified as overweight or obese according to their BMI.

For example, Saxenda (liraglutide), a drug that blunts appetite by mimicking the glucagon-like-peptide (GLP-1) hormone, is available to anyone in the UK with a BMI of 30 and over, or to patients with a BMI of 27 to 30 if they have another weight-related co-morbidity (such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol or sleep apnoea).10

This blanket guidance allows GPs and other healthcare professionals to determine who is eligible for medication, however, this may mean that people with dangerously high levels of body fat are unable to access the drug, and conversely, those with low body fat percentages with a high BMI would technically be eligible.

While there clearly needs to be rules in place to prevent people of a healthy weight accessing the medication (which could fuel eating disorders), critics argue that body composition should also be a key factor when considering who is eligible for weight loss medication.

In a commentary published in the AMA Journal of Ethics, Astrid Floegel-Shetty argues that relying on BMI as an indication of health poses various problems when it comes to prescribing pharmaceutical weight loss treatments.

Floegel-Shetty argues that when evaluated for physical and metabolic fitness, those classified as overweight or obese (BMI > 25) will not necessarily be at risk of poor health.

“Research on the ‘obesity paradox’ and ‘metabolically healthy obesity’ substantiates the existence of this incongruence between the expected and actual health or risk status associated with an obesity diagnosis,” she writes.

“Additionally, the clinical distress of obesity can exist in bodies that do not match the expected phenotype of obesity (i.e. fat), which are described in literature as thin-fat phenotype, normal weight obesity, metabolic obesity, and metabolically unhealthy non-obese.”11

Floegel-Shetty therefore concludes that there is no general consensus for what constitutes a healthy BMI, and “BMI and weight as defining clinical metrics distort our conception of what is required for health.”

She argues that “physicians might be inaccurately assessing the benefits as outweighing the risks in prescribing pharmaceuticals to induce weight loss”, and instead calls for “weight-neutral and weight-inclusive approaches” where weight status is just one factor informing our understanding and pursuit of health.11

Online availability of weight loss drugs could fuel eating disorders

It could therefore be argued that clinicians should consider multiple factors before prescribing weight loss medication, including the individual’s weight, body fat percentage, muscle mass and bone density.

If a DXA scan is not available, there are other methods which can be used to measure body fat (such as skinfold calipers, waist circumference and waist to hip ratio).

This is particularly pertinent at a time when weight loss drugs are increasingly being sold via online pharmacies, when all the patient needs to do is fill out an online form.

Eating disorder charities have repeatedly highlighted the danger of prescribing weight loss medication online, and warn that such medications should only be sold under the strictest conditions.12

References

- Lahav Yair, Kfir Aviv, Gepner Yftach. The paradox of obesity with normal weight; a cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Nutrition. Vol 10. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1173488/full

- Fletcher, I. (2014), Defining an epidemic: the body mass index in British and US obesity research 1960–2000. Sociol Health Illn, 36: 338-353.

- Muscle density vs fat – how they affect your weight. Stride Strong. 2023. Available at: https://stridestrong.com/muscle-density-vs-fat/

- How useful is body mass index (BMI)? Medical News Today. 2023. Available at: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/255712

- DXA body composition analysis. UC David Health. Sports Medicine. Available at: https://health.ucdavis.edu/sports-medicine/resources/dxa-info

- Clynes MA, Westbury LD et al. International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) and the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF). Bone densitometry worldwide: a global survey by the ISCD and IOF. Osteoporos Int. 2020.

- Suhaili, Abdulrahim. The Middle East & Africa Regional Audit, Epidemiology, costs & burden of osteoporosis in 2011. 2011. Available at: http://www.iofbonehealth.org/download/osteofound/filemanager/publications/pdf/Middle-East-audit-11/ME_audit.pdf

- British Heart Foundation. What’s the best way to measure body fat? N. D. Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/heart-matters-magazine/nutrition/weight/best-way-to-measure-body-fat

- How Body Fat Percentage Can Trick You. 2019. Available at: https://www.revolutionptwl.com/about/blog/53/How-Body-Fat-Percentage-Can-Trick-You

- NICE recommended weight-loss drug to be made available in specialist NHS services. 2023. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/news/article/nice-recommended-weight-loss-drug-to-be-made-available-in-specialist-nhs-services

- Floegel-Shetty, Astrid. Should Pharmaceuticals Be Used as Weight Loss Interventions for Adolescents Classified as Obese by BMI? AMA J Ethics. 2023;25(7):E478-495. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2023.478.

- The Guardian. Online UK pharmacies prescribing weight loss jabs to people with healthy BMI. 2023. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/may/10/online-uk-pharmacies-prescribing-weight-loss-jabs-to-people-with-healthy-bmi-investigation