Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

Case study: renal abscess and back pain

This case study reviews a older patient who presented with an enormous and enlarging renal abscess causing unrelenting back pain and difficulty ambulating.

Abstract

Renal abscesses are commonly caused by an ascending urinary tract infection. Our patient presented with a mass on her back that had grown over five weeks and excruciating left flank pain. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) showed a large 20cm left renal abscess demonstrating posterior perinephric extension into the subcutaneous soft tissues of the abdominal wall. Cultures of fluid from this abscess grew E. Coli. This mass drained massive amounts of purulent fluid with a Jackson-Pratt drainage left in place.

We treated her with antibiotic therapy for almost one month. Our patient was unable to ambulate because of the severe pain from this abscess.

In conclusion, renal abscesses can present with excruciating back pain as the main complaint. In addition, urinary symptoms are not always seen in clinical practice. Lastly, the size of the abscess can grow gradually over weeks and be easily palpable on exam.

Introduction

A renal abscess is commonly a complication of a urinary tract infection. This may be from some blockage of urine output allowing an ascending bacterial organism to infect the kidney. Common risk factors include recurrent urinary tract infection, nephrolithiasis, intravenous drug use, kidney disease, permanent urinary catheter, and urologic instrumentation.

Treatment usually involves intravenous antibiotics, and drainage for abscesses larger than 3cm or for abscesses that don’t resolve with antibiotic treatment.1 Empiric treatment includes fluoroquinolones, third-generation cephalosporins, broad-spectrum penicillins, and aminoglycosides. Antibiotic therapy can also be specified based on culture sensitivities. The risks include significant morbidity and mortality from complications such as sepsis or rupture to the renal pelvis.1

Case presentation of renal abscess

Our patient is a 76-year-old female with history of hypothyroidism, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, bipolar disorder, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, breast cancer status post mastectomy, who presents with five weeks of progressive left flank pain and growing mass. Of note, the patient felt a growing mass over her left flank and went to her primary care doctor, at which time he thought it was a lipoma. However, the mass became more painful and grew in size.

The patient was in agonising back pain and unable to ambulate or lay flat. She had mild nausea, abdominal discomfort, dyspnea, dry cough, worsening bilateral leg swelling, and gained eight-pounds over a week. She had subjective chills, but no fever. She denied dysuria, frequency, or hematuria. Vitals on admission included a temperature of 98.3 Fahrenheit, heart rate 74 beats per minute, blood pressure 156/64mmHg, and saturation of oxygen 96% on room air. Physical exam was significant for a large fluctuant tender retroperitoneal mass over the left flank that was non-erythematous, but warm, and bilateral 2+ pitting oedema extending to the mid-shins.

Initial diagnosis/assessment

Labs were significant for White Blood Cell Count 26.81 k/UL, Creatinine 0.50 mg/dL, Serum Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide: 3287 pg/mL, and Thyroid Stimulating Hormone, Serum: 2.62 uIU/mL. Urinalysis showed White Blood Cells 4/high power field (hpf), Red Blood Cells 5/hpf, Epithelial Cells 11/hpf, many bacteria, moderate leukocyte esterase, and positive nitrites.

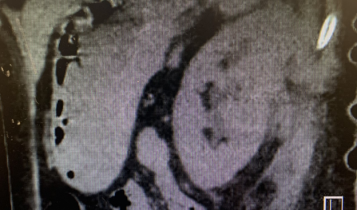

Blood cultures were negative. MRI of the abdomen with contrast showed a large 20cm left renal abscess with posterior perinephric extension into the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1).

Cytopathology from the abscess drainage was negative for malignant cells, but showed abundant acute inflammatory exudate. Culture of the abscess drainage grew moderate E. Coli with multiple morphological strains. Given the patients left flank pain, cytopathology findings of acute inflammatory exudate, growth of E. Coli from the purulent drainage fluid, and massive renal abscess on imaging, a left renal abscess due to E. Coli was the most likely diagnosis.

Treatment/management

Interventional radiology drained the abscess and left a Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain in place for further collection. The patient was initially started on intravenous Zosyn (piperacillin/tazobactam) antibiotics and switched to IV ceftriaxone while inpatient. Patient was discharged on oral cefitin as for a total of 30 days. JP drained over 100-200 cubic centimeter (cc) per day for the first few days which then decreased to 10-90 cc per day later on. Urology saw the patient and deemed no need for inpatient surgery.

Outcome and implications

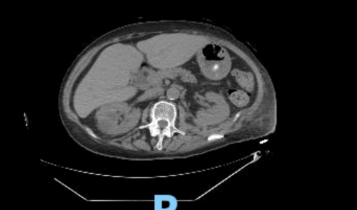

Repeat imaging showed near complete resolution of the previously seen left renal abscess after drainage and prolonged antibiotic therapy (Figure 2A and 2B). Patient made a significant recovery and was discharged to a rehabilitation facility with close follow up.

Discussion

Suppurative infections of the kidney can certainly occur, especially in older adults with multiple comorbidities. Both renal and perinephric abscesses start with local inflammatory oedema and complement activation that leads to tissue necrosis. If left untreated, they can cause significant morbidity and mortality.

In a study done by Lee et al of 56 patients with renal abscess, the mean age was 53.5 years, and a female predominance (75%) was observed. The average duration of symptoms was 11.6 days.2 Another study done by Rai et al of 2278 patients showed an equal predominance of abscesses among males and females.3

The most common pathogens causing renal abscess are gram negative uropathogens including, E. Coli (44%) and Klebsiella (28%). Approximately two-thirds of renal abscesses caused by these organisms occur in patients with a renal stone or vesicourethral reflux.4 Renal abscess should be suspected in patients with pyelonephritis who don’t respond to antibiotics. In the pre-antibiotic era, hematogenous spread of Staphylococcus Aureus was the most common cause of infection 2 with intravenous drug use being a common risk factor. 5

In a Korean study of 56 patients with renal abscesses, the most common symptoms were fever (75%), chills (63%), abdominal pain (46%), anorexia (38%), and dysuria (9%). 1 The average duration of symptoms prior to admission was just 12 days.

Imaging of renal abscesses can easily be done with ultrasound or CT scan.6 MRI is more expensive and unnecessary unless there is high clinical suspicion of malignancy.7 Cultures of the fluid for cytopathology can also be very useful.

Successful treatment of renal abscess involves prolonged intravenous or oral antibiotic therapy, or percutaneous drainage in case of antibiotic non-responders or very large abscesses. For renal abscesses less than 5cm, antimicrobial therapy alone is the best initial management.

In a study done of 52 patients with renal abscesses, resolution was observed in 100% of patients with abscesses less than 3cm, and 92% of patients with abscesses that were 3 to 5cm.8 For renal abscesses greater than 5cm, antimicrobial therapy and percutaneous drainage are both usually necessary. Percutaneous drainage is preferred over surgical intervention because of decreased morbidity and mortality. Urologic intervention is indicated in cases of urologic obstruction, anatomic abnormalities, or very large abscesses that cannot be drained.

Conclusion

In summary, renal abscesses can have differing presentations, and excruciating back pain may be the only complaint. The pain can be so severe that patients may be unable to ambulate or even lay down flat. Furthermore, abscesses can present as a progressively enlarging mass to very large sizes (as large as 20cm in this patient) and cause symptoms for over a month. These masses should be investigated with cytopathology.

E. Coli is a very common culprit in renal abscesses, but urinary symptoms of infection, including lower urinary tract infection, and pyelonephritis may be absent. Percutaneous drainage will demonstrate very purulent material, and a drain may need to be in place for several weeks for resolution in cases of very large abscesses. Prolonged antibiotic therapy and percutaneous drainage may be very successful in resolving the abscess.

Jack Jnani, Department of Internal Medicine, North Shore University Hospital. 300 Community Drive, Manhasset, New York 11030

Hanna Freyle, Department of Internal Medicine, North Shore University Hospital. 300 Community Drive, Manhasset, New York 11030

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained in the writing of this report, and personal identifiers were not used in compliance with privacy regulations.

Conflict of interest: The authors report no conflict of interest in the writing of this report.

Financial disclosure: There were no sources of funding used in the writing of this manuscript.

References

- Novak J, Vik V, Zachoval R, Bjerklund Johansen TE. (2016). Renal abscess caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-Producing bacteria and complicated by the perforation to a cyst and to the renal pelvis.Journal of Endourology Case Reports, 2(1), 123-126.

- Lee BE, Seol HY, Kim TK, et al. (2008). Recent clinical overview of renal and perirenal abscesses in 56 consecutive cases. The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine, 23(3), 140.

- Rai R, Karan S, Kayastha A. (2007). Renal and perinephric abscesses revisited. Medical Journal Armed Forces India, 63(3), 223-225.

- Anseli ID. (1990). Uropathology (Vols 1 and 2). G. S. Hill (Ed.). Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, 1989. No. of pages: 1400. Price: £195. ISBN: 0 443 08194 8. The Journal of Pathology, 160(4), 362-362.

- Hoverman IV. (1980). Intrarenal abscess. Report of 14 cases. Archives of Internal Medicine, 140(7), 914-916.

- Demertzis J, Menias CO. (2007). State of the art: Imaging of renal infections. Emergency Radiology, 14(1), 13-22.

- Meng M.V, Mario LA, McAninch JW. (2002). Current treatment and outcomes of perinephric abscesses. The Journal of Urology, 1337-1340.

- Siegel, JF, Smith A, Moldwin R. (1996). Minimally invasive treatment of renal abscess. The Journal of Urology, 52-55.