Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

Abstract

Background

Benzodiazepine and Z-drugs have effective anxiolytic and sedative properties and are widely used in the management of anxiety disorders. Whilst the risks of dependence and dose escalation of these drugs have been well described, these risks were not reflected in our day-to-day clinical experiences of older adult patients suffering with anxiety disorders in secondary care.

Aim

This study aims to scrutinise benzodiazepine and Z-drug prescriptions, including frequency, duration, dose and patterns which may or may not support evidence of dependence.

Method

We conducted a retrospective review of 251 electronic patient records for all older adults referred to secondary care with anxiety symptoms, over a one-year period.

Results

We identified a high prevalence of sedative-hypnotic use, with a large proportion prescribed them for over four weeks. Doses above recommended daily limits were in the minority. The majority of benzodiazepine and Z-drug prescriptions (87.5% and 86.6% respectively) were either discontinued, reduced or unchanged in dose.

Conclusions

Our observations may add to evidence that long-term use is not synonymous with dependence and dose escalation. Careful consideration should be given to the view that long-term use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in anxiety disorders is always harmful and leads to dependence. By stigmatising sedative-hypnotic drug use, we could prevent older adults obtaining therapeutic benefits from these medications.

Introduction

Benzodiazepines are hypnotic drugs that enhance the activity of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).1 Zolpidem, zopiclone and zaleplon are non-benzodiazepine hypnotics that share a similar mode of action but are chemically distinct;1 they are commonly known as Z-drugs.

These medications have effective anxiolytic, sedative and hypnotic properties and are commonly used in anxiety disorders.2 From the 1980s, however, concerns regarding their propensity for dependence and abuse started to rise, with a particular concern over the vulnerability of older adults to this problem.2

Many suggest the risk of physiological and psychological dependence among elderly persons increases with age so their use should be discouraged and benzodiazepines should be stopped wherever possible.3 Treatment guidelines for anxiety and insomnia, therefore, caution against benzodiazepine and Z-drug use as first-line or long-term therapy, and uninterrupted use should not exceed four weeks.4-6

There is a high prevalence of sedative-hypnotic use in adults over the age of 65 years, and a common perception their use leads to abuse, tolerance and dependence.7 Research indicates the average age of people being prescribed these drugs is approximately 66.7

A study in 2015 identified approximately 40% of benzodiazepine long-term prescribing was for people aged over 80.8 This compared to approximately 20% of long-term prescribing in patients in their twenties and thirties.8

There is also a possible higher percentage of benzodiazepine misuse in older adults – one study suggesting 17% compared with 3% in younger people.8 An older study by Whitcup et al9 suggested 21% of patients over the age of 65 admitted to a psychiatric unit had a diagnosis of substance dependence, a majority of whom were dependent on benzodiazepines.

The risk of benzodiazepine addiction may also be more likely to occur in women and people with low income, chronic pain, difficulty with everyday activities, social isolation and anxiety.10

It is important to clarify the terms used to describe substance use disorders. Abuse is drug use with the aim to achieve a ‘high’, and not for therapeutic benefits.11 Misuse is a deviation in use from the prescription.12 Dependence is a syndrome, characterised by compulsion, impaired control, withdrawal, tolerance, preoccupation and persistent use of the substance despite known harm.13 Tolerance results in increased doses of the substance being needed to achieve the effect originally produced by lower doses, or a much-reduced effect if using the same amount.13

‘Abuse’, ‘misuse’, and ‘dependence’ are often used without clarity regarding their meaning, yet the implications and the challenges that come with them have significant implications. Misuse should not be mistaken for abuse – the majority of patients ‘misusing’ prescribed medication are doing so to control symptomatic distress, and their use may restore the individual to a functioning life.12

Long-term use should not be considered synonymous for misuse, abuse and dependence; and there is a growing body of evidence suggesting not all patients who take benzodiazepines for long periods become dependent.7

A study by Pinsker & Suljaga-Petchel14 assessed the prevalence of benzodiazepine use in older adults and did not find cases of abuse, however this study is now quite out-dated, limited by multiple exclusion criteria and dependent on self-reporting of amount and frequency of use. Some evidence does indicate, however, that long-term treatment with benzodiazepines is associated with maintenance of beneficial effects, and dose escalation is not seen.12 O’Brien15 argues only a few cases of dependence arise from the legitimate use of benzodiazepines, and their use should not be stigmatised.

Aims/objectives

Whilst the risks of these drugs have been well described, we were not noticing emergence of dependence or dose escalation in our patients. We completed a review of benzodiazepine and Z-drug prescribing, over a 1-year period, for our older population with anxiety disorders in secondary care. The aims and objectives are to:

- Identify the proportion of older people with anxiety disorders prescribed these drugs, how long they are prescribed for and at what doses.

- Expose any clear patterns of prescribing supporting dependence.

- Add contemporary evidence to the debate surrounding their use.

Ethical approval

This study was registered with and approved by Hertfordshire Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust (HPFT) Practice Audit and Clinical Effectiveness (PACE) team. It made use of information collected as part of routine care, and therefore did not require formal ethics committee approval.

Method

The Specialist Mental Health Service for Older Adults (SMHSOP) delivered by HPFT delivers mental health services to more than 0.195 million adults over the age of 65 in Hertfordshire, covering a wide mix of urban and rural areas.

A retrospective review of electronic patient records (EPR) for all older adults open to SMHSOP in 2019, with a recorded ICD-10 diagnosis of F40-F48 (neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders), was conducted.

Each case was investigated to collect:

- Demographic data – age and gender

- Diagnos(es)

- Dose of any benzodiazepine or Z-drug prescription on referral, for less than 4 weeks, 4 weeks-6 months, over 12 months and on discharge (if applicable)

Data was cross-referenced against General Practice (GP) records using shared record viewer (SRV). All doses were converted into a percentage of British National Formulary (BNF) recommended daily dose for that drug. For any missing data, a last data carried forward approach was used.

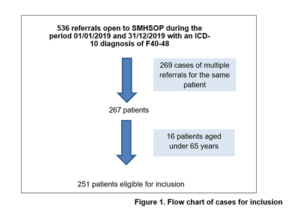

A total of 536 referrals were open to SMHSOP, this amounted to a sample size (n) of 251 cases once multiple referrals and those aged less than 65 were excluded (Figure 1).

Results

Demographics

183 of patients in the study were female with a mean age of 80.2 years (age range 67-101 years, SD 7.6). 68 were male, with a mean age of 77.5 years (age range of 67-98 years, SD 7.4). The most common diagnostic category was F41, Other Anxiety Disorders.

Prescriptions

61.0% (n=153) of all patients eligible for inclusion were prescribed benzodiazepines or Z-drugs. 39.4% (n=99) were prescribed benzodiazepines and 17.9% (n=45) were prescribed Z-drugs, whilst 7.9% (n=9) were prescribed both concurrently.

Lorazepam and diazepam were the most commonly prescribed benzodiazepines, combining to 84.9% of cases (Figure 2). Zopiclone was the Z-drug of choice in 93.3% of cases (Figure 3).

Duration and dose

Over three quarters of patients (76.7%) prescribed benzodiazepines and over two thirds of patients (66.7%) prescribed Z-drugs were prescribed them for ≥4 weeks.

14 cases (14.1%) of benzodiazepine prescriptions and 5 cases (11.1%) of Z-drugs prescriptions were over the BNF recommended daily dose.

Prescribing patterns

10 cases (10.1%) of benzodiazepine prescriptions and 4 cases (8.8%) of Z-drug prescriptions showed an increase in dose.

In 70/80 cases (87.5%) where benzodiazepines were already prescribed, and 26/30 cases (86.6%) where Z-drugs were already prescribed, they were discontinued, reduced or unchanged in dose.

Discussion

This review identified several interesting findings. Firstly, more than 60% of patients were prescribed benzodiazepine or Z-drugs. This is over five times higher than the 12% reported in the community sample by Johnson et al.16 The mean age of patients was 78.9 years of age. This supports the study by Bogunovic & Greenfield,7 which suggests there is a high prevalence of sedative-hypnotic use in adults over the age of 65. We found that women were prescribed these medications more than men, which is in keeping with other literature.8

Diazepam, lorazepam and zopiclone were the mostly commonly used medications. This is possibly due to familiarity and Trust trends. The popularity of zopiclone use may be linked with its known lower cost. The NHS indicative price from AAH Pharmaceuticals is £1.12 for 28 tablets at 50% BNF recommended daily dose for zopiclone, compared with £2.56 for 28 tablets at 50% recommended daily dose for Zolpidem.4

Older adults tend to have an increasing sensitivity to side effects of medication due to altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics with advancing age.17 Diazepam has an estimated average half-life of 100 hours, as compared with lorazepam of 15 hours, and so may be more likely to accumulate in an older body and cause prolonged effects.17

In addition, increased sensitivity in older people due to age-related receptor changes in the central nervous system may occur.18 These can both result in greater effects and side effects, such as increased sedation, unsteadiness, falls and confusion, particularly if higher doses are used.18

There is, however, a risk that side-effects have been overestimated and the long-term therapeutic benefits have been underestimated. A systematic review of papers researching falls in older adults taking sedative-hypnotics observed that, whilst benzodiazepine use is associated with a higher risk of falls, this is often dose related, such as overdose, and higher in the first 24-120 hours following initiation of the drug.19

In addition, their side profile can be considered more favourable than the long-term use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and antipsychotics, which can also cause falls and sedation, and many non-psychiatric drugs also have a higher risks of falls attached.19

Both benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are cautiously recommended as short-term treatments (less than 4 weeks) for insomnia and anxiety.4-6 Whilst the diagnostic sample characteristics are in keeping with the indications for use, the duration of prescribing significantly exceeds this for the majority of cases. Indeed, in a large proportion of cases prescribing exceeds one year.

Despite evidence of long-term prescribing, there were only a minority of cases where doses exceeded the maximum BNF recommended daily dose. Additionally, in the majority of cases, medication doses were either discontinued, reduced or unchanged. This was the same for both benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (87.5% and 86.6% respectively).

A key component of dependence syndrome is tolerance.13 Tolerance results in increased doses of the substance being needed to achieve the effect originally produced by lower doses.13 If tolerance and dependence were developing, a reverse pattern of dose escalation might have been observed.

Our review may add to the growing body of evidence that long-term benzodiazepine and Z-drug use may have a role in managing anxiety disorders. Long-term use is not synonymous with dependence and might support patients’ restoration to more functional lives. Individuals may be obtaining long-term prescriptions for ongoing therapeutic benefit without dose escalation being observed, and their use should not be stigmatised.

Limitations of review

As this review solely obtained doses of medications, which were converted to a percentage of BNF recommended daily dose, we are unable to comment on clinical aspects of other features of dependence or misuse. For example, we have not gathered detail on reported side effects, whether patients are demonstrating compulsion to take substances, evidence of withdrawal states or previous history of substance misuse.

The study is also limited by a small sample size. Despite starting with 536 referrals this amounted to 251 cases to investigate. When looking at more detail in prescribing patterns of these drugs, for Z-drugs this amounted to a sample size of only 45 patients. Due to the small sample available, subgroup analysis exploring the impact of patient demographics or type of drug on prescribing patterns was not possible.

Conclusions

- Careful consideration should be given to the view that long-term use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in anxiety disorders is always harmful and leads to dependence.

- Stigmatising sedative-hypnotic drug use could be preventing older adult populations obtaining ongoing therapeutic benefits from these medications.

- The risk of tolerance and dependence may be overestimated; identifying who is at risk could help individualise treatment.

- In view of the increasing sensitivity to side effects of medication due to altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in older adults, education to prescribers could be helpful to reduce the use of drugs with longer half-lives, such as diazepam, which are more likely to accumulate and cause prolonged effects in the older population.13

- Future work scrutinising the types of medication used may shed light on which medications are associated with dose escalation.

- Details of the clinical consultations where benzodiazepine and Z-drug prescribing decisions are being made, particularly where the drug is being increased or prescriptions are rising above the BNF recommended daily dose, could provide further insights.

- The experience and perspectives of patients who use these drugs regularly would be beneficial to obtain, to help identify if any negative aspects of the drugs are offset by an improvement in quality of life.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

Dr Katherine Witter, ST5 Specialist Registrar in Older Adult Psychiatry, Specialist Mental Health Services for Older Adults, Hertfordshire Partnership University Foundation Trust

Dr Lauren Redding, ST5 Specialist Registrar in Older Adult Psychiatry, Mental Health Liaison Team, Hertfordshire Partnership University Foundation Trust.

Dr Rahul Tomar, Consultant in Older Adult Psychiatry, Specialist Mental Health Services for Older Adults, Hertfordshire Partnership University Foundation Trust.

Prof Tim Gale, Research lead for Hertfordshire Partnership University Foundation Trust, UK and visiting Professor at the University of Hertfordshire.

References

- Stahl S. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 5th Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2021

- Singh S, Sarkar S. Benzodiazepine abuse among the elderly. Geriatr. Ment. Health 2016; 3(2):123-130

- Lader MH. Interviewed by: Waite J. Benzodiazepines. Face the facts. BBC Radio 4. July 21 1999, 21.00pm.

- Joint Formulary Committee. Hypnotics and anxiolytics. In: Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. [BNF online]. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press; 2016. Available from: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/hypnotics-and-anxiolytics/

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guidance on the use of Zaleplon, Zolpidem and Zopiclone for the short-term management of insomnia. Technology Appraisal 77. NICE; 2004. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11530/32845/32845.pdf

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Generalised anxiety disorder in adults: management in primary, secondary and community care. National Clinical Guideline 113. NICE; 2011 Available from: nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13314/52667/52667.pdf

- Bogunovic OJ, Greenfield SF. Practical geriatrics: use of benzodiazepines among elderly patients. Serv. 2004; 55(3): 233-235

- Farias JC, Porter L, McManus S, et al. Prescribing patterns in dependence forming medicines. NatCen Social Research, London; 2017. Available from: http://phrc.lshtm.ac.uk/ papers/PHRC_014_Final_Report.pdf

- Whitcup SM, Miller F. Unrecognized drug dependence in psychiatrically hospitalized elderly patients. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1987;35: 297-301

- Chatterjee D, Iliffe S, Kharicha K, et al. Health risk appraisal in older people 7: long-acting benzodiazepine use in community-dwelling older adults in London: is it related to physical or psychological factors? Primary Health Care Research & Development 2017; 18: 253- 260

- MaustDT, Lin LL, Blow FC. Benzodiazepine use and misuse among adults in the United States. Serv. 2019; 70: 97–106

- Silberman E, Balon R, Starcevic V, et al. Benzodiazepines: it’s time to return to the evidence. J. Psychiatry 2021; 218(3): 125-127

- World Health Organisation (WHO). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. WHO 1993: Geneva, 70-83

- Pinsker H, Suljaga-Petchel K. Use of benzodiazepines in primary-care geriatric patients. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1984; 32: 595-597

- O’Brien CP. Benzodiazepine use, abuse, and dependence. Clin. Psychiatry 2005; 66(2): 28–33

- Johnson CF, Frei C, Downes N, McTaggart SA, Akram G. Benzodiazepine and z-hypnotic prescribing for older people in primary care: a cross-sectional population-based study. J. Gen. Pract. 2016; 66(647):e410-5

- Cook PJ. Benzodiazepine hypnotics in the elderly. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. Supplement 1986; 55(3): 149-158.

- McLachlan AJ, Pont LG. Drug metabolism in older people-a key consideration in achieving optimal outcomes with medicines. Gerentol. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 2012; 67(2): 175-180

- Díaz-Gutiérraz MJ, Martínez-Cengotitabengoa M, Sáez de Adana E, et al. Relationship between the use of benzodiazepines and falls in older adults: A systematic review. Maturitas 2017;101(7): 17-22