Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

Ageing well? Where next for older people’s care

At the GM Conference 2022, Tom Gentry, Senior Health Influencing Manager (policy), Age UK, spoke about the current issues facing the NHS, the impact of Covid on older people and what we can expect from the NHS and older people’s care in 2023.

At the GM Conference 2022, Tom Gentry, Senior Health Influencing Manager (policy), Age UK, spoke about the current issues facing the NHS, the impact of Covid on older people and what we can expect from the NHS and older people’s care in 2023.

NHS Long Term Plan

“The future of the NHS as a whole centres on delivering better care for older people,” Mr Gentry says, and this was a key focus of the NHS Long Term Plan (published in 2019).

Under these plans, the NHS said they would shift as much care as possible out of the hospital and into the community by preventing care needs emerging in the first place and delivering more care in people’s homes (or close by).

To support this, the NHS introduced various measures, including expanding primary care networks, making greater use of urgent care centres and better utilising digital technologies.

But Mr Gentry says there are some fundamental needs that haven’t been met under these plans, for example, the needs of frail, older adults. This could be tackled with the introduction of an acute frailty service that provides care for least 70 hours a week. This would eventually achieve a clinical frailty assessment within 30 minutes of arrival.

The Ageing Well programme

The Ageing Well programme was designed to focus specifically on the needs of older adults. It aims to help older people manage long-term conditions, and ensure sure they receive the right kind of support. This can be broken down into three stands, Mr Gentry says: anticipatory care, urgent community response and enhanced health in care homes.

- The anticipatory care programme aims to get care to people more quickly and have more joined up coordinated teams, led by multiple professionals in the community to anticipate need and to make sure that someone is getting the best care they can to maintain wellbeing and their level of health.

- The urgent community response service aims to bolster rapid crisis response services and ensure patients are seen within two hours of referral. This can be done within the home or in a care setting, enabling a much quicker response time and avoiding hospital admission wherever possible.

- The enhanced health in care homes programme was developed to address the long-standing challenge with the under provision of healthcare in care homes, and better coordinate care efforts for older people who, traditionally, are not given the service they need.

There are many other key mechanisms that are important to mention, including the NHS Right Care Frailty Pathway, the Community Directed Enhanced Service, the Frailty Core Capabilities Framework, the NHS People Plan and social prescribing.

However, the Covid-19 pandemic significantly disrupted these plans, making them much more challenging to implement. To discover exactly how health and care services for older people were affected, Age UK conducted a combination of representative polling with people aged 60+, as well as various surveys between Covid waves one and five, which each generated responses from around 15,000 people.

Impact of COVID

The survey’s results reveal that in the summer of 2021, around a quarter (24%) of older people said their health had got worse, with half (55%) of this group saying they were not confident their health would improve.

Health and wellbeing were also affected, with around 41% saying they were lonely (37% said they spent less time with family and 23% spoke to their family less) and one third (33%) saying they felt more anxious.

Cognition and dementia were also negatively impacted, with around a quarter (23%) of older people saying they found it harder to remember things. Long Covid and brain fog were also frequently reported, while some said dementia appeared to ‘speed up’ with no social contact or support.

More people began to care for loved ones too, with 28% saying they were providing care for a family member, partner or friend. However, most struggled, and 83% said they were worried about whether they could continue caring, 49% said they were tired and 40% said they were anxious.

There was also a general sense of rapid ageing, and many said they felt they had lost their freedom, confidence and spontaneity, and often experienced feelings of grief and anger. Some said they felt like they were ageing more quickly and running out of time.

One respondent said: “I feel the ageing process has rapidly advanced in the past 18 months. I have started going to restaurants and some shops, but I have slowed down quicker than I should have.”

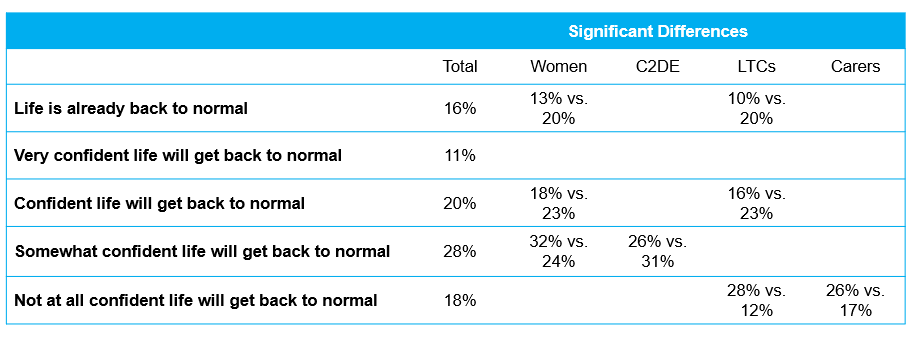

In Spring 2022, Age UK asked older people and carers how confident they were about life returning to ‘normal’. Around half (46%) were only somewhat confident or not confident at all that life will get back to normal.

“These stats give a sense that any positivity or optimism about the future just didn’t really exist within the samples that we spoke to,” Mr Gentry said. “The role of carers is critical in maintaining wellbeing and managing health in a way that means they can’t deteriorate. I think that’s a very stark message for all of us.”

Where next? The NHS into 2023

Last year, as we came out of the pandemic, the government and the NHS worked together to form new policies which have set the ground work for what the health and care landscape will look like throughout 2023.

One of the most significant policies was the Health and Social Care Act. This legislation has seen integrated care boards take over from clinical commissioning groups, with the expectation that there will be much more coordinated care across larger geographical areas. The NHS will work with local authorities and public health colleagues to do more population level work expected of the NHS and social care system.

The Fuller Review, which looked at what needs to change to better meet the population’s care needs, was also published, as well as a move towards virtual wards (or hospital at home), rapid response falls teams and a discharge support fund to ensure people are able to be cared for in the community as soon as possible.

The NHS has also published early plans for a new intermediate care service and the government said it would refresh the Long Term Plan, although it is not clear when this will be published.

Social care is set to face a set of unique challenges, with huge pressure on local authority budgets and operating margins on care homes disappearing. The energy crisis is hitting particularly hard in the not-for-profit sector, meaning that some of the care home provision that has been relied on for years and maybe starting to recede even faster than it was before.

This problem has been exacerbated by the workforce crisis in social care. In October 2023, it was reported that there were more than 165,000 vacancies across the sector. This lack of staff has meant there are fewer people to care for those in the community, and hospitals are therefore being more heavily relied upon.

While the lifetime cap on care costs is due to be introduced in October this year, it is now unclear where the funding for this plan will come from, after the social care levy was scrapped by Truss’ government.

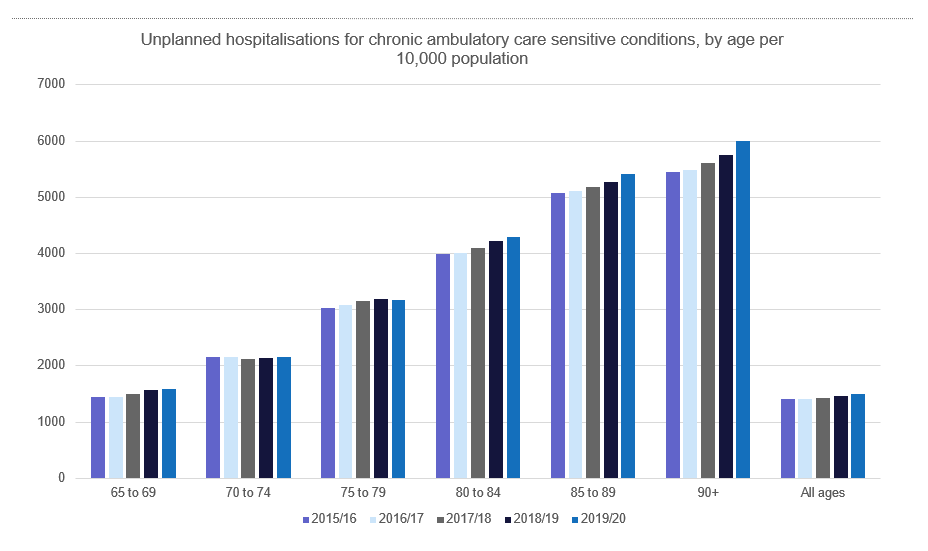

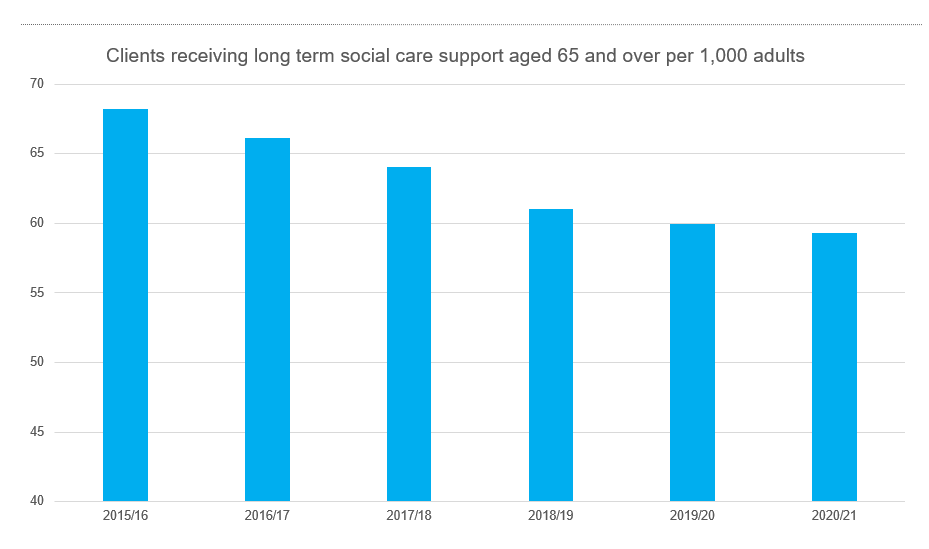

Many of these issues predated the pandemic, and the number of unplanned hospitalisations for chronic ambulatory care sensitive conditions has been rising steadily since 2015, while the number of people receiving social care support has been steadily declining. This is likely to be linked to the rising number of people attending hospital with unmet needs.

Why can’t I get care? Older people’s experiences of care and support

Age UK has recently published a new report, Why can’t I get care? Older people’s experiences of care and support, which looked at older people’s experiences of accessing health and social care.

Social care at home was the most cited issue, with carers saying they do not have access to the support they need, and this is having an impact on their health.

One respondent said: “My caring role is horrendous. It’s very, very difficult. There’s so many things I have to support Michael with, and my own health is not good”.

Others said the care they were receiving was invasive rather than supportive. One respondent said they would “rather die on their own” than have the care provided because of the nature of the support on offer.

Many said they had unmet needs, and fewer people felt supported to manage their condition. For example, some felt GPs did not try and pursue a potential diagnosis. Others did receive a diagnosis, but felt they weren’t given suitable follow up care.

One said: “But every time there was no prognosis, no medication given. [My GP] said: ‘What do you expect? You’ve got some gel, you’ve got some painkillers, that’s all I can do for you’”.

Some also felt they were not listened to, and serious health concerns were not taken seriously. One person said they had a broken hip for five or six weeks, yet no one took any action to provide them with the care they needed, while another was diagnosed with a chest infection, when they really had a fractured spine.

“Once you’re a certain age, you are a nuisance,” one respondent said. “Very often it seems you are swept under the carpet.”

Care staff felt just as frustrated as patients, with most desperate to do more. One respondent said the situation was “dire” and staff are often “in tears” due to the lack of help they are able to provide patients.

Ultimately, although these challenges existed before the pandemic, staff felt that the pandemic bought these challenges to the fore. A geriatrician who responded to the survey said: “These things have been there and have been brewing for a long time. We have been burying our heads in the sand and the pandemic just exposed it all I think.”

How can we get to a better place?

In order to improve the current climate, Age UK says we urgently need lasting change in social care, and this will require sustainable and fair funding from the government.

The charity would also like to see the government “invite” social care to the table so that it is unified with healthcare under the new integrated care systems framework.

We also need to equip primary care for an older and ageing population and ensure that care and support planning is centred on goals that are meaningful to older people, Mr Gentry said

“We have to move beyond piecemeal change. It’s no good to just do a few programmes here and there. We need to look at the whole piece and see what big changes can be made,” Mr Gentry concludes.

If you missed out on getting a ticket for the GM Conference 2022, it’s not too late. You can access recordings of the full CPD-certified conference using our online conference hub. To find out more, please contact [email protected].