Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

Managing PCOS in primary care

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) can have a devastating impact on quality of life, and early diagnosis is key. But there is still a lack of awareness and understanding about this life-long condition, reports Kathy Oxtoby.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) can have a devastating impact on quality of life, and early diagnosis is key. But there is still a lack of awareness and understanding about this life-long condition, reports Kathy Oxtoby.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a very common endocrine condition that affects one in 10 women in the UK. It manifests differently in each individual and can be devastating to their self-esteem and quality of life. There is no known cause or cure.1

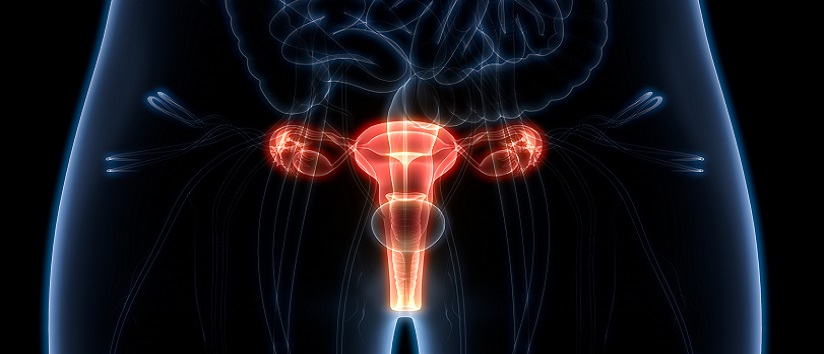

What is PCOS?

The main features of PCOS are irregular periods, excess androgen – “male” hormones which may cause physical signs such as excess facial or body hair when found in high quantities – and polycystic ovaries, where the ovaries become enlarged and contain many follicles that surround the eggs. 2

Despite the name, women do not actually have cysts if they have PCOS.2

[rml_read_more]

“PCOS is a problematic name and causes many barriers to treatment and to understanding the condition,” says Rachel Morman, who was diagnosed with PCOS aged 24, and is trustee of PCOS charity Verity.

The name of the condition and its diagnosis criteria – known as the ‘Rotterdam criteria’ – are set to be discussed at the Androgen Excess & PCOS Society (AE-PCOS) meeting of international researchers in Rotterdam this October.

While the exact cause of PCOS is unknown, it often runs in families and is related to abnormal hormone levels in the body, including high levels of insulin.2

Diagnosing PCOS

It is unclear if the condition is becoming more prevalent or if it is just better detected and diagnosed now.

Until the early 2000s, “we didn’t really have diagnostic criteria”, says Dr Bassel Wattar, consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist at Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust, and a senior researcher at University College London.

All this changed when the Rotterdam criteria was introduced in 2003, which has “facilitated a much easier diagnosis”, he says.

The Rotterdam criteria states that two of the following must be present for diagnosis:

- Irregular or no ovulation;

- Excess androgens and/or physical signs of this;

- Polycystic ovaries.3

Late diagnosis is an issue for those with PCOS, says Dr Wattar, and often, this only comes when women are unable to get pregnant, and are referred to a specialist.

PCOS signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of PCOS will “vary from person to person”, says Professor Stephen Franks, professor of reproductive endocrinology at Imperial College London.

Signs and symptoms include irregular, infrequent or absent periods, unwanted body hair, persistent acne, and alopecia. For women who are having infrequent or absent periods, their fertility is likely to be diminished because they are ovulating less frequently, he says.

Women with PCOS are more prone to put on weight, due to a hormonal imbalance, says Dr Wattar.

PCOS is also associated with an increased risk of developing health problems in later life, such as type 2 diabetes and high cholesterol levels.2

However, more than half of women with PCOS do not have any symptoms.2

Impact of PCOS

PCOS can have “a huge impact” on individuals and varies from person to person, says Ms Morman. “It has a range of symptoms that affect how you walk through the world, and your sense of identity.”

This complex condition “affects people very differently” she says. “For example, if you are someone who wants to have children and PCOS affects your reproductive ability to have children, the affect can be devastating and life-long. Or if PCOS involves hair loss, it could have a massive impact on your confidence. And hormone fluctuations can affect your mood,” she says.

There is also the impact of menstrual irregularity. “I bled every day for 18 months and became very anaemic,” says Ms Morman. “Prior to that, I had no bleeding for four years. PCOS can make you question your body, and how much confidence you have in your body. Sometimes it’s like you’re a stranger within your own body because you don’t understand what’s going on and how to change things and predict what’s going to happen,” she says.

Research into the impact of PCOS on women’s mental health suggests those with the condition are more prone to anxiety and depression, says Professor Franks.

Studies also suggest individuals with PCOS are more likely to take early retirement, to experience unemployment, and to have problems with their physical health, such as being prone to musculoskeletal problems.4,5,6

While PCOS is a lifelong condition “adoption of early interventions can really minimise its impact”, says Dr Wattar.

How is PCOS managed?

The wide spectrum of presentation means that the management of PCOS will be different, and it is important for GPs to know when to refer to a specialist, says Professor Franks.

Treatment will depend on what symptoms are most prominent, he says. If someone is trying to get pregnant and is only having a few periods a year, it is important they are referred to a fertility clinic.

If they have slightly irregular periods and are troubled by unwanted hair, they can be referred to a specialist, and their condition may be treated with the contraceptive pill to reduce the amount of androgen in circulation.

Similarly, if they have irregular cycles and heavy bleeding but are not trying to get pregnant, this could also be treated with the contraceptive pill.

Given the wide spectrum of symptoms PCOS covers, “it’s important to look at symptom clusters and consider the appropriate management for a particular patient”, says Professor Franks.

To manage PCOS, practitioners need to “really understand women’s health needs, which can change throughout their life”, says Dr Wattar.

He says that, for example, a young woman with PCOS may not be looking to get pregnant so may find it more acceptable to take the oral contraceptive pill, while someone keen to become pregnant may need help with their fertility. And a woman with PCOS going through the menopause may be at higher risk of diabetes and need to manage their diet.

To minimise the impact of PCOS, practitioners can advise patients on “simple interventions to help them enjoy a healthy life”, such as dietary advice. But those interventions need to be made in a “timely fashion”, and there needs to be “early diagnosis”, says Dr Wattar.

Signposting to support and advice

Practitioners can signpost to sources of advice and information about PCOS, such as the AskPCOS app, and the PCOS charity Verity.

Peer support is also important when dealing with PCOS, and practitioners can signpost people to Verity’s website for further information about how to connect with, and meet others dealing with the same condition.

“Peer support is an underrated source of help for people to connect with others who know what you’re going through, and can be incredibly valuable,” says Ms Morman.

There is still a lack of awareness among practitioners about what support is available to individuals with PCOS and more quality education about the condition is needed, says Dr Wattar.

He says another challenge to supporting those with PCOS is the “fragmented” way care is provided in the NHS, meaning that symptoms are addressed in silo by, for example, physicians, gynaecologists and dieticians.

Dr Wattar would now like to see dedicated PCOS clinics in the NHS offering multi-disciplinary care from one site.

Practitioners need to consider “the life course impact of PCOS as a chronic condition and think: ‘How can I help the patient to learn more and empower then to manage their condition themselves in the community, and how can I reduce the barriers for them to access the care they need’,” says Dr Wattar.

PCOS “should be taken seriously, because it can have multiple effects, and recognising and treating it early is important,” says Professor Franks

It is also important for practitioners to understand that PCOS is a “lifelong condition that affects the individual differently through their life stages,” says Ms Morman.

“They must be cognisant of this diagnosis – that they might be seeing them for other issues later down the line. And they need to look at the individual, and consider where to refer and to signpost to support groups such as Verity,” she says.

She says PCOS is “not just a reproductive condition, and practitioners shouldn’t just be telling people to ‘go away, lose weight, and come back when you want to have a baby’, which is a common thing that we hear”.

And, crucially, she says practitioners need to have empathy with those living with PCOS, remembering that it can have “a devastating impact on an individual’s quality of life”.

Resources· International evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (2018) (This guideline is due to be updated later this year) · NICE Polycystic Ovary Syndrome [last revised February 2022] · The Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society: an international organisation dedicated to promoting the generation and dissemination of knowledge related to all aspects of Androgen Excess Disorders · Verity: A self-help group for those with PCOS · AskPCOS: App to help women with PCOS find more information on the condition. |

References

- Verity (2017) What is PCOS? Available at: http://www.verity-pcos.org.uk/

- NHS (2022) Polycystic ovary syndrome. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos/

- Verity (2017) How do you get diagnosed with PCOS? Available at: http://www.verity-pcos.org.uk/diagnosing-pcos.html

- Karjula S et al (2020) Population-based Data at Ages 31 and 46 Show Decreased HRQoL and Life Satisfaction in Women with PCOS Symptoms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Jun 1;105(6):1814–26. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz256. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31970392/

- Karjula S et al (2017) Psychological Distress Is More Prevalent in Fertile Age and Premenopausal Women With PCOS Symptoms: 15-Year Follow-Up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Jun 1;102(6):1861-1869. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3863. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28323926/

- West S et al (2014). The impact of self-reported oligo-amenorrhea and hirsutism on fertility and lifetime reproductive success: results from the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966. Hum Reprod. 2014 Mar;29(3):628-33. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det437. Epub 2013 Dec 8. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24324025/