Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

Intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) has been the cornerstone of treatment for patient with acute ischaemic stroke who fulfill the inclusion criteria and have no contraindications for it.1 In more recent years, mechanical thrombectomy in combination with IVT has become the gold standard treatment for stroke patients caused by large vessel occlusion (LVO).

Large vessel occlusion (LVO) is the obstruction of large, proximal cerebral arteries and accounts for up to 38% of acute ischaemic stroke.2 In patients with acute ischemic stroke with LVO in anterior circulation, namely proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA) and distal internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusion, evidence shows limited response to IVT alone.

One group of researchers found that in patients with acute middle cerebral artery stroke, thrombus length can predict the likelihood of a successful recanalisation post IVT. If it is less than 5mm, there is a high chance that it will dissolve completely; however, there is only 1% chance to dissolve a clot that is over 8mm long.3 There is also a high risk of re-occlusion within two hours of IVT in those who achieved complete or partial recanalisation after IVT.4

What is mechanical thrombectomy?

Mechanical thrombectomy involves using a specially-designed clot removal device inserted through a catheter to pull or suck out the clot to restore blood flow.10

In 2015, there was a paradigm shift in acute ischaemic stroke treatment where mechanical thrombectomy was introduced as add on therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke and LVO in proximal circulation who presented within therapeutic time window (4.5 hours) or mechanical thrombectomy alone if patient presented within 6 hours of onset of symptoms.6-9

When used with other medical treatments on a specialist unit, evidence shows thrombectomy can significantly reduce the severity of disability a stroke can cause. Although only a relatively small number of stroke patients (around 1 in 10) are suitable for this treatment, for those that are, it is a very powerful intervention. It is able to remove clots which are too big to be broken down by clot-busting drugs and is therefore effective in preventing and reducing long-term disability in people with severe strokes.10

Currently, only a fraction of those eligible for mechanical thrombectomy actually get it. It is estimated that around 9,000 patients a year could benefit from it in the UK but it is thought that fewer than 10% of those eligible actually receive it. There are a few centres where thrombectomy is available in the UK but there are not enough trained professionals for the services to be rolled out across the country.10

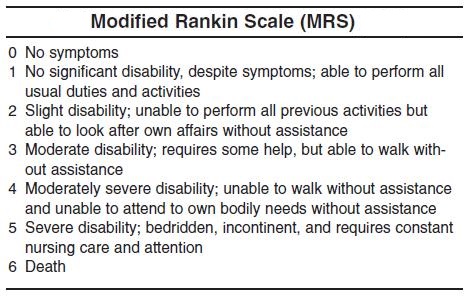

The number of patients who required to be treated with endovascular thrombectomy in order to reduce impairment by at least one level on the Modified Rankin Scale was about 3.6

Thrombectomy is at least as safe as other treatments. Studies have shown that, on average, mechanical clot retrieval does not cause any greater risk of death, bleeding or secondary stroke, compared to other types of stroke treatment.10

NICE guidance on mechanical thrombectomy

As per NICE guidelines, thrombectomy for people with acute ischaemic stroke is to be offered as soon as possible if their pre-stroke functional status is less than 3 on the Modified Rankin Scale,9 they have a score of more than 5 on the National Institutes of Health of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and confirmed occlusion of the proximal anterior circulation demonstrated by computed tomographic angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). This is in addition to one of the following:

- They presented within 4.5 hours of symptoms onset of acute stroke (intravenous thrombolysis to be given prior to thrombectomy)

- Last known to be well between 6 hours and 24 hours previously (including wake‑up strokes) and there is the potential to salvage brain tissue, as shown by imaging such as CT perfusion or diffusion-weighted MRI sequences showing limited infarct core volume.

- Last known to be well up to 24 hours previously (including wake‑up strokes) and there is the potential to salvage brain tissue, as shown by imaging such as CT perfusion or diffusion-weighted MRI sequences showing limited infarct core volume.

Timing of mechanical thrombectomy

Stroke is a devastating disease for the patient and family and is estimated to cost the NHS around £3bn per year, with additional cost to the economy of a further £4 billion in lost productivity, disability and informal care. About 20% of patients die within the first year (and the majority of these patients die within the first three months) and over 50% of survivors are left with long-term disability.11

A disproportionately high share of the disability burden arises within the 30-50% of patients with proximal large artery occlusive stroke. Many of these patients will have a mixture of cognitive, mood and physical function problems.11

Time is a key factor in acute ischemic treatment that influences response to therapy. In a patient with ischaemic stroke due to anterior circulation LVO, every minute delay in revascularisation results in the brain losing two million neurons, which is 14 billion synapsis an hour. This is the same number of neurons that is lost in approximately four years of normal ageing.12

While thrombolysis can only be given up to four and a half hours after a stroke, NHS England has approved thrombectomy for use up to six hours after stroke symptoms begin. There are some very specific and rare circumstances in which thrombectomy may be given up to 12 or even 24 hours after the onset of stroke. In addition, there is ongoing research to explore longer time windows in carefully selected patients.10

For patients receiving IVT, the number needed to treat (NNT) is 5 if treatment is initiated within 1.5 hours of symptom onset, which is nearly doubled to 9 if treatment is initiated within 1.5-3 hours of symptom onset. It increased to 15 if treatment is started within 3-4.5 hours of symptoms onset.13

Healthcare professionals can not control time of onset of symptoms (TOS) or time of hospital arrival (TOH), However, we can control TOH to time of CT head performance (TOC) and subsequently thrombolysis and thrombectomy performance. Focusing on reducing this time is expected to have a good outcome for patients.

Majdah AL Rushaidi, Trust Doctor at James Cook University Hospital, Department: Old Person Medicine (OPM)

References

- Chugh, C. Acute ischemic stroke: management approach. Indian journal of critical care medicine: peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine, 2019; 23: S140

- Sweid A, Hammoud B, Ramesh S, et al. Acute ischaemic stroke interventions: large vessel occlusion and beyond. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2019 Nov 28;5(1):80-85. doi: 10.1136/svn-2019-000262

- Riedel CH, Zimmermann P, Jensen-Kondering U, et al. The importance of size: successful recanalization by intravenous thrombolysis in acute anterior stroke depends on thrombus length. Stroke 2011; 42: 1775-1777

- Alexandrov AV, Grotta JC. Arterial reocclusion in stroke patients treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. Neurology. 2002 Sep 24;59(6):862-7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.6.862. PMID: 12297567.

- Goyal M, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. The Lancet 2016; 387, 1723-1731

-

Zhang J, Yuan C, Deng X, et al. Efficacy and safety of endovascular treatment with or without intravenous alteplase in acute anterior circulation large vessel occlusion stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurol Sci. 2022 Jun;43(6):3551-3563. doi: 10.1007/s10072-022-06017-8. Epub 2022 Mar 22. PMID: 35314911.

- Saver JJ, Goyal M, Bonafe E, et al. Stent-Retriever Thrombectomy after Intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA Alone in Stroke. New England Journal of Medicine 2005; 372: 2285-2295.

- Berkhemer OA, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2005; 372, 11-20

- NICE. Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng128

- Stroke Association. What we think about: Thrombectomy. https://www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/new_pdfs_2019/our_policy_position/psp_-_thrombectomy.pdf

- NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Mechanical-thrombectomy-for-acute-ischaemic-stroke-ERRATA-29-05-19.pdf

- Saver JL. Time is brain—quantified. Stroke 2006; 37: 263-266

- Lees KR, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. The Lancet 2010; 375 1695-1703